Part 4 of this series

The titular question may sound trivial at first glance. Of course he’s capable (i.e., not incapable) of ruling over anyone or anything, from anywhere, as long as his Father wills it, right? Yet Pulliam insists that it’s impossible for Jesus to reign on Earth: “there are reasons why He actually cannot rule upon the earth” {“In the Days of Those Kings: A 24 Lesson Adult Bible Class Study on the Error of Dispensationalism”. Pulliam, Bob. 2015. Houston, TX: Book Pillar Publishing. 93. Italics and boldface in original.}. His two proof-texts are Zechariah 6:12-13 & Jeremiah 22:28-30. My responses to each of these proof-texts are somewhat involved, so I’ll focus on them one at a time.

Zechariah 6:12-13

“12Then say to him, ‘Thus says the Lord of hosts, “Behold, a man whose name is Branch, for He will branch out from where He is; and He will build the temple of the Lord. 13Yes, it is He who will build the temple of the Lord, and He who will bear the honor and sit and rule on His throne. Thus, He will be a priest on His throne, and the counsel of peace will be between the two offices.”’”

(Zechariah 6:12f)

In this prophecy, the Messiah (who is the Branch of David – see Jer 23:5) will “build the temple of the Lord.” Not only that, he will “sit and rule on his throne.” The Lord then draws the two offices of priest and king together by saying that “He will be a priest on His throne.” Obviously, the Messiah will be priest and king at the same time.

These offices (king and priest) are held concurrently, therefore we can draw this simple conclusion: Since Jesus is presently our great High Priest, then He also must presently be our king. Fulfillment of Zechariah 6:12-13 may be found in the current priesthood and reign of Jesus. And this truly agrees with what we discovered in lesson 8. Namely, that Jesus is presently seated on the throne of David.

Dispensationalists acknowledge that this passage teaches a concurrent reign and priesthood of Jesus; however, they tell us that it will not take place until the future Millennium.…

Hebrews 8:4 says, “Now if He were on earth, He would not be a priest at all, since there are those who offer the gifts according to the Law”. This is based on a previous argument concerning Jesus being from the tribe of Judah (Heb 7:13f). Since Jesus was not from the tribe of Levi, He cannot be a priest on earth. So let’s briefly revisit the theory that Jesus will be a king and priest in a future earthly Millennium. The inspired author of Hebrews tells us that it cannot happen. Jesus cannot be a priest on earth so long as Levites offer their gifts. According to Dispensationalism, Levites will be offering sacrifices in the Millennial temple.

The heavenly ministry of Jesus was God’s intention from the beginning. This is evident from the design of the tabernacle. The author of Hebrews tells us that it and its service was patterned after the heavenly places (Heb 9:1-8, 23-24). The earthly tabernacle and temple were just a shadow of good things to come (Heb 8:5 & 10:1). Jesus has now fulfilled that heavenly design by entering into the very presence of God. This is one aspect of His high priesthood that makes Him far superior to the Old priesthood. Dispensationalists want us to abandon the substance of our heavenly priest, and return to a shadow (a priest on earth). According to the Dispensational view of the kingdom, Jesus will leave heaven, returning to the weak and worthless elemental things (Gal 4:9f). This certainly is not the step forward that they would present it as being.

Why would the tabernacle foreshadow a current condition (Jesus in heaven) if the Millennial temple on earth is supposed to be the true substance? The Dispensationalist says the Millennium will be the prophesied time of great peace. However, Zechariah’s “counsel of peace” resting upon two concurrent offices cannot exist with Jesus on earth, according to the author of Hebrews. This conflict with Dispensationalism is extremely revealing. Jesus’ present position in the Holy of Holies, which is heaven, speaks volumes regarding His throne and God’s purpose (Heb 9:23f; 10:1). The message of Hebrews clearly reveals that we have the good things foreshadowed in the Old Testament (cf. Heb 10:1).

The author of Hebrews also defined the function of a high priest when he said that “every high priest taken from among men is ordained for men in things pertaining to God, that he may offer both gifts and sacrifices for sins” (Heb 5:1). Jesus is in heaven interceding for us through His blood (Rom 8:34; Heb 10:19). In other words, He has made peace through His blood (Eph 2:13f; Col 1:20). And it is in the office of His priesthood that this peace is provided, but it can only be provided by His presence in heaven, not on earth. If He does come back to earth, He cannot be a priest (Heb 8:4), and the prophecy of Zechariah 6 would be broken. Remember, the counsel of peace shall be between both offices. He must be a king and priest at the same time. Zechariah does not give us the luxury of splitting off an office (high priest) for a few thousand years, and then adding the Messiah’s rule. The “counsel of peace” is now, or never.

…[In Lesson 12:] Let’s begin with the great hope held out for all families of the earth: “And in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” (Gen 12:3) This is part of the covenant God made with Abraham. … Peter clearly announced the fulfillment in his own day. [See his discussion on Acts 3, quoted early on in and debunked further into this post] Jesus fulfilled the blessing promise as the great Messianic King.

Nowhere is this connection between blessing and king better seen than Zechariah 6:12-13. We studied this passage in lesson 9. It prophesied a Messiah who would be a priest at the same time that He ruled. The blessing of forgiveness came through Christ’s present priesthood. But He also rules upon His Messianic throne.

{“In the Days of Those Kings”. 93-96, 127-128. Italics and boldface in original. Underlining and contents in brackets mine.}

Let’s set aside the observations that the word usually rendered “elements” in Galatians 4:9 refers to the foundations of human civilization, not the building blocks of the universe (i.e., the material universe won’t be “weak and worthless” in the New Heavens & New Earth!); and that the epistle to the Galatians dealt with Judaizers who were trying to turn Christians back to observance of the Mosaic Covenant, which will be done away with in the New Heavens & New Earth (comparing the sacrifices laid out in Leviticus with those of Ezekiel 40-48 shows that the sacrifices prophesied in the latter passage won’t be made according to the Mosaic Law — the “Law” being referred to in Hebrews 8:4).

On that note, Pulliam’s remark that “Jesus cannot be a priest on earth so long as Levites offer their gifts” creates a problem for his own view that the Mosaic Law has been permanently done away with and will never be revived: Levites haven’t offered their gifts since A.D. 70. So if Pulliam is correct that the Law those gifts are offered in accordance with will never be revived, then how does this argument from the author of Hebrews that Jesus can’t be a priest on earth because he’s from the tribe of Judah instead of Levi not go out the window for the period of time since A.D. 70?!

My answer is as follows: The Mosaic Law is still in effect at present, but it’s only binding on ethnic Israelites who haven’t entered into the New Covenant. The Mosaic system, offerings and all, will be revived during the apocalypse (Daniel 9:27a, Revelation 11:1), but the Ark of the Covenant will have been taken out when the Abomination of Desolation shows up (Revelation 11:19), preventing the high priest from visiting it on Yom Kippur for the second half of the apocalypse. The Holy of Holies housing the Ark of the Covenant being replaced with Jesus’ throne (i.e., the throne of David) in the Kingdom temple (Revelation 21:22, cf. Jeremiah 3:16-17; see also Ezekiel 43:1-7) tells us that the Mosaic regulations regarding the Ark and the Holy of Holies will be done away with, once and for all, upon Jesus’ return.

Anyway, let’s refocus on the point at issue here. Notice the sheer number of arguments Pulliam makes that hinge on the premise that Zechariah taught that the Messiah would be a king and priest concurrently. This makes it all the more interesting that he appeals to the author of Hebrews, who consistently talked about Jesus’ priesthood as present, but his kingship as future! In fact, he went so far as to distinguish (quoting OT prophecy to do so, no less!) the periods of time when Jesus would have these roles. Have you ever noticed how some passages in most English Bibles use the term “forever” or “for ever”, but then you come across other passages in the same translation with “forever and ever” or “for ever and ever”? The latter phrasing isn’t superfluous, nor is it simply a dramatic flourish on the part of the writer/translator; rather, the underlying Greek phrasing actually features a repeated term. Consider these two verses from Young’s Literal Translation of Hebrews that are germane to the subject we’re considering in this blog post: “and unto the Son: ‘Thy throne, O God, is to the age of the age; a scepter of righteousness is the scepter of thy reign;” (1:8, boldface and underlining added; quoting Psalm 45:6 LXX) “and he with an oath through Him who is saying unto him, ‘The Lord sware, and will not repent, Thou art a priest — to the age, according to the order of Melchisedek;’” (7:21, boldface added; quoting Psalm 110:4 LXX). The Greek phrase in the latter case (referring to Christ’s priesthood) is εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα (“unto/for the age”), but the Greek phrase in the former (referring to Christ’s being seated on David’s throne) is εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα τοῦ αἰῶνος (“unto/for the age of the age”).1 It’s certainly feasible to take “for the age” as meaning “during the Christian era”, and “for the age of the age” as meaning “during Christ’s 1,000-year reign on Earth”. But can Pulliam offer an alternative explanation for this distinction within Hebrews (which is borne out in the OT phrasing of the verses the author was quoting)?

Evidently, the author of Hebrews himself didn’t see Zechariah as prophesying Jesus holding these roles concurrently!

The Author of Hebrews’ Track Record Comes In Clutch

But how can that be, in light of the clear phrasing Pulliam brings out from the 1995 NASB? Well, bear in mind that the NASB is following the Masoretic Text here (which, incidentally, doesn’t include the word “offices”; the end of the Hebrew sentence — בֵּין שְׁנֵיהֶם — literally reads “between both” or “among two”, and we’ll see below that the Septuagint substantially agrees with either or even both of these renderings), and that Zechariah 6:12-13 hasn’t been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. One thing the author of Hebrews seems to have had an amazing knack for (in hindsight) was using the Septuagint version of the OT to make points to his 1st-century Jewish Christian audience that couldn’t have been made with the Hebrew text we have today. Examples include the quotation “And let all the angels of God worship him” (Hebrews 1:6c KJV), which appears nowhere in the Masoretic Text, but does occur in Deuteronomy 32:43 LXX (and the Dead Sea Scrolls have further corroborated the LXX reading here); and the rhetorical question “For unto which of the angels said he at any time, Thou art my Son, this day have I begotten thee?” (Hebrews 1:5a KJV), where his audience evidently couldn’t respond by pointing to Job 1:6, 2:1, or 38:7, where the Masoretic Text refers to angels in general as “the sons of God” — because the 1st-century Hebrew text of the Job passages had “angels” instead of “sons”, just like the LXX does {scroll to p. 33-37 in the PDF}!

So is it possible that the author of Hebrews emphatically contradicting Pulliam’s conclusion from Zechariah 6:12-13 is another example of the former making a point (Jesus being high priest and king during two separate periods of time) that can’t be made with the modern Hebrew text? Is it possible that none of the original readers of Hebrews could raise the point Pulliam does, simply because the phrase Pulliam’s relying on wasn’t in the text until after their time? In a word: yes.

Here’s the Greek text for these 2 verses; the boldfaced phrase reads וְהָיָה כֹהֵן עַל־כִּסְאוֹ (“and so he will be / a priest / on–his throne” — my right-to-left translation) in the Masoretic Text:

καὶ ἐρεῖς πρὸς αὐτόν τάδε λέγει κύριος παντοκράτωρ ἰδοὺ ἀνήρ Ἀνατολὴ ὄνομα αὐτῷ καὶ ὑποκάτωθεν αὐτοῦ ἀνατελεῖ καὶ οἰκοδομήσει τὸν οἶκον κυρίου καὶ αὐτὸς λήμψεται ἀρετὴν καὶ καθίεται καὶ κατάρξει ἐπὶ τοῦ θρόνου αὐτοῦ καὶ ἔσται ὁ ἱερεὺς ἐκ δεξιῶν αὐτοῦ καὶ βουλὴ εἰρηνικὴ ἔσται ἀνὰ μέσον ἀμφοτέρων (Zechariah 6:12-13 LXX, boldface added)

Now here’s my word-by-word translation, with slashes to indicate the spaces between the Greek words:

And / you will say / toward / him, / “These things / says / the Lord, / Sovereign Over All: / Behold! / A man, / Dayspring / is the name / for him. / And / from beneath / Him / will he rise, / and / he will build / the / house / of the Lord. / And / he / will take to himself / virtue, / and / certainly seat himself, / and / will make reconciliation / upon / the / throne / of his. / And / there will be / the / priest / out from / the right / of him, / and / counsel / which is peaceable / will be / amidst / the middle / of both.” (boldface added)

You see the difference this makes regarding the priest and the man on the throne, right? They’re not the same person! You can’t be to the right of yourself! Don’t think my translation’s legit? Compare it with Brenton’s:

and thou shalt say to him, Thus saith the Lord Almighty;

Behold the man whose name is The Branch; and he shall spring up from his stem [Gr. from beneath him.], and build the house of the Lord. And he shall receive power[lit. virtue.], and shall sit and rule upon his throne; and there shall be a priest on his right hand, and a peaceable counsel shall be between them both. (BLXX, boldface added; contents in brackets are from Brenton’s footnotes indicated at those points in the text)

Think Brenton was wrong too? Check out the more modern NETS (New English Translation of the Septuagint) rendering, published online in 2009 {scroll to p. 40 in the PDF}:

And you shall say to him: This is what the Lord Almighty says: Behold, a man, Shoot [Or Dawn] is his name, and he shall sprout from below him and shall build the house of the Lord. And it is he that shall receive virtue and shall sit and rule on his throne. And the priest shall be on his right, and peaceful counsel shall be between the two of them. (NETS, boldface added; content in brackets are from the footnote indicated at that point in the text)

And as long as the church I currently attend, the Archdale Church of Christ, happens to have a copy of the Lexham English Septuagint (arguably the one official English translation of the Septuagint that’s most independent of all the others), why not include its rendering for good measure?

And you will say to him, ‘This is what the Lord Almighty says: “Behold, a man; Anatole [Meaning “east” or “dawn”; Heb. “Branch”] is his name, and from beneath him he will rise up and build the house of the Lord. And he will receive virtue, and he will sit and rule upon his throne, and the priest will be out of his right, and there will be a peaceful plan between both. (LES, boldface added; content in brackets are from the footnote indicated at that point in the text)

The main reason for this overwhelming consistency is that the Greek word we’re all rendering “right” is δεξιῶν, the genitive plural form of δεξιός (dexios, G1188), an adjective meaning “right” (as opposed to “left”, not “wrong”). The root word behind dexios is very common in Indo-European languages. In fact, two Octobers ago, I got new glasses, and when looking over the prescription I noticed the initials O.D. & O.S.; these are abbreviations for the Latin phrases “oculus dexter” and “oculus sinister“, respectively meaning “right eye” and “left eye”.

The Septuagint version of this passage clearly says that at the time of its fulfillment, the two offices of king and priest would be occupied by two different people! When Jesus is to be king, someone else will be the priest at Jesus’ right side! Suddenly, all the statements throughout Hebrews implying that Jesus isn’t to be a high priest and king of kings concurrently make perfect sense! The author of Hebrews was able to conclude that Jesus would be high priest and king at two separate times because, at the time he wrote, no available reading of any Biblical passage taught otherwise!

With this, all of Pulliam’s arguments based on his interpretation of Zechariah 6:12-13 fall apart. (And by accepting the Masoretic reading of Zechariah 6:12-13 along with its implications, dispensationalists have forced a contradiction into their theological system.) It’s worth adding that the Septuagint version of Jeremiah 23:5 (which Pulliam cited as a cross-reference to the Zechariah passage) also has “Dayspring” instead of “Branch”, so that cross-reference remains valid, despite the different connotations associated with the two titles (which are themselves brought out in the Masoretic and Septuagint versions of Zechariah 6:12b). Indeed, the title used in the Septuagint version of these passages is invoked by Zacharias near the end of the prophecy he gave at the circumcision of his son, John the Baptist:

Yea and thou, child, shalt be called the prophet of the Most High:

For thou shalt go before the face of the Lord to make ready his ways;

To give knowledge of salvation unto his people

In the remission of their sins,

Because of the tender mercy of our God,

Whereby the dayspring from on high shall visit us,

To shine upon them that sit in darkness and the shadow of death;

To guide our feet into the way of peace. (Luke 1:76-79 ASV, boldface added)

So now let’s move on to Pulliam’s other proof-text.

Jeremiah 22:28-30

28 “‘Is this man Coniah a despised, shattered jar? Or is he an undesirable vessel? Why have he and his descendants been hurled out And cast into a land that they had not known? 29 O land, land, land, Hear the word of the Lord!’ 30 Thus says the Lord, ‘Write this man down childless, A man who will not prosper in his days; for no man of his descendants will prosper sitting on the throne of David or ruling again in Judah.’”

(Jeremiah 22:28-30)

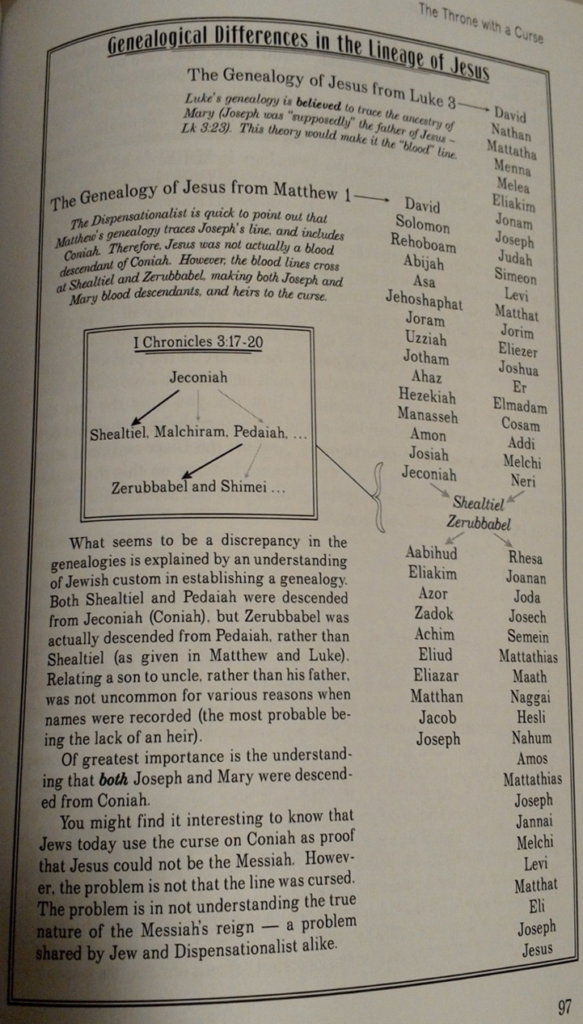

Coniah was a king in the genealogy of Jesus. He was also known as Jeconiah (Jer 24:1; 27:20). This passage is of great importance because of the curse that it places upon Jeconiah’s descendants. It begins with “Write this man down childless…” (v30). The point is not that he would have no children, because he actually did (I Chr 3:17). The point was that no descendant of Jeconiah would be able to prosper while ruling in Judah. And bear in mind that this includes Jesus (Mt 1:11-12).

So how can Jesus be the highly anticipated King of Glory, if a curse was placed upon His bloodline? The curse itself only affects Jesus if He is reigning in Judah. The significance, in Jesus’ case, is that He can rule in heaven, but He cannot rule on earth. …

The Dispensationalist has a clever way of trying to answer Jeremiah 22. They contend that the genealogy in Matthew and Luke both descend from David, but one is through Solomon (Matthew), and the other is through Nathan (Luke). The line that descends from Solomon contains the name Jeconiah, but the line descending from Nathan does not. The argument attempts to make the “blood line” of Luke exclude the curse on Coniah. Since Joseph was only the “legal” father, the curse of Coniah in his line (Matthew’s account) would not affect Jesus.

Without the slightest thought to what the genealogy of Luke really tells us, the Dispensationalist has missed the incredible significance of the post-captivity portion of the genealogy (see chart on the previous page). While it is true that Luke’s genealogy does not contain Jeconiah, it does contain the descendants of Jeconiah. How can you miss the fact that Jeconiah’s son is Shealtiel, and his grandson is Zerrubabbel, [sic] and that both of these men are in both genealogies? And yet the Dispensational argument is made as proof that the curse has no bearing on this discussion. In all honesty, it must have everything to do with this discussion, because Jesus is in the blood line of Jeconiah. …

If you talk to an orthodox Jew, He will argue that Jesus couldn’t possibly have been the Messiah. That is no surprise, but his use of Coniah’s curse is interesting. You see, he understands that Jesus’ bloodline cannot be split as the Dispensationalist tries to do. The line of Solomon and the line of Nathan criss-cross at Shealtiel and Zerrubabbel. [sic]

I make the same argument to the Jew that I make to the Dispensationalist. The curse only affects a descendant who rules upon the earth in the tribal territory of Judah. Jesus does not rule upon the earth in Judah. His throne is in heaven, and it is the throne of David promised to Him by the Father. …

Jesus, being a descendant of Coniah, cannot rule in Jerusalem and prosper. This is not a problem for God’s plans, because He never intended for His Messiah to reign on Earth. As Peter clearly taught in Acts 2, Jesus is presently on the throne of David; however, it is a rule from heaven.

{“In the Days of Those Kings”. 96,98-99. Italics, boldface, and indentation in original. Underlining mine.}

Aside from the fact that Peter placed Jesus’ reign in the future from his own time in Acts 2 and the fact that the dispensationalists’ explanation regarding the different genealogies has been the most common one throughout the Christian era, this argument that Jesus’ reign will never be on Earth seems pretty intimidating on the surface. Yet, Pulliam includes a footnote during this discussion that considerably undermines his own arguments — and it gives me an opportunity to “make the same argument to the Jew that I [can] make to the” amillennialist!

Walvoord, Every Prophecy, pp 127f. This is a highly speculative area. Why there are differences between the genealogies of Matthew and Luke is a question never explicitly answered by scripture. There are several good reasons for these differences, and one of the most popular is to understand each genealogy as leading down to Joseph and Mary individually. But which genealogy leads to Joseph, and which to Mary? Not everyone agrees. (cf. Marshall D. Johnson, “Genealogy of Jesus,” ISBE, Vol II, p430). The Dispensationalist must assume that Matthew’s genealogy leads to Joseph, so the curse of Coniah does not fall directly upon Jesus (by blood). But as I have pointed out, both lines include Coniah. Of great interest is the Jewish view of these genealogies, which would deny that Jesus had any right to the throne of David by a “step-father.” Jews argue that blood alone did not give a descendant the Messianic right (cf. Asher Norman, 26 Reasons Why Jews Don’t Believe In Jesus, Reason 8). The father’s line had to be the blood line. That argument not only assumes which gospel offers the blood line, but also refuses to allow for the fact that Jesus was not just another man born in Israel. Jesus, being begotten of God, was a rightful heir directly from His identity as Jehovah. This same stumbling block to first century Jews remains for present day Jews who deny the validity of any evidence of Jesus’ identity. {“In the Days of Those Kings”. 98(Fn5). Italics and boldface in original. Underlining mine.}

Pulliam really doesn’t see the web he’s entangled himself in here, does he? First off, if the father’s line had to be the blood line, and the father had to be in the royal line, then wouldn’t the curse on Jehoiachin (whose male descendants would include the royal line) disqualify anyone from ever being the Messiah? Jews who reject Jesus as the Messiah undercut their own belief in the “real” Messiah’s eventually coming by using this argument! Second, Pulliam acknowledges that many of the arguments orthodox Jews have presented against Jesus’ messiahship were originally formulated using circular reasoning — that is, they assumed from the outset that Jesus wasn’t the Messiah {p. 99}, and then they tried to construct arguments that would specifically disqualify Jesus from being the Messiah! But how does Pulliam know that the argument that “The father’s line had to be the blood line” wasn’t in that category? Third, note his statement that “Jesus, being begotten of God, was a rightful heir directly from His identity as Jehovah.” How does this point alone not render the question of which line is the blood line (Joseph or Mary’s; the one in Matthew or the one in Luke) totally moot?! Finally, note that he claims that “both lines include Coniah”, despite the fact that he admitted that the name “Jeconiah” occurs in Matthew’s genealogy, but not Luke’s. He tries to explain this more thoroughly in the following diagram on p. 97:

(If you’re using a browser that can have music playing in a different tab while you read this post, I recommend clicking here before you read the next section!)

Okay Pulliam, SEVERAL Things…

Notice that he totally ignored the fact that Luke’s account says that Shealtiel was the son of (literally, was “from”) Neri, not Jeconiah! Would Pulliam explain this the same way he explains the relationship presented between Shealtiel and Zerubbabel in 1 Chronicles 3:17-20? If so, then he has to assume that Matthew is giving the “bloodline” and Luke isn’t (so much for his attempt to use Occam’s Razor by claiming he’s making the fewest assumptions — which he repeatedly tries to drive home with terms like “highly speculative area”, “[n]ot everyone agrees”, “must assume”, “assumes which gospel offers the blood line”, and “is believed to“)! But contrary to Pulliam’s insistence that all such explanations for which is the bloodline are “speculative”, we can actually tell that’s not the case because checking Kings and Chronicles reveals that the genealogy in Matthew has gaps between David and Jeconiah (Matthew 1 lists 14 generations from David to Jeconiah, but Kings and 2 Chronicles present 18 generations between them; hence, Matthew’s list is selective, and Matthew 1:17 shows that this selectiveness was intentionally done as a memory device)! Actually, the 1 Chronicles passage gives us enough Biblical information to justify a better explanation for the evidence Pulliam has brought forward in this diagram:

The sons of Yekhonyah, the captive: She’alti’el his son,

and Malkiram, and Pedayahu, and Shenazzar, Yekamyah, Hoshama, and Nedavyah.

The sons of Pedayahu: Zerubbavel, and Shim`i. The sons of Zerubbavel: Meshullam, and Hananyah; and Shelomit was their sister;

and Hashuvah, and Ohel, and Berekhyah, and Hasadyah, Yushav-Hesed, five.

The sons of Hananyah: Pelatyah, and Yesha`yah; the sons of Refayah, the sons of Arnan, the sons of `Ovadyah, the sons of Shekhanyahu.

The sons of Shekhanyahu: Shemayah. The sons of Shemayah: Hattush, and Yig’al, and Bariach, and Ne`aryah, and Shafat, six.2

The sons of Ne`aryah: Elyo`enai, and Hizkiah, and `Azrikam, three.

The sons of Elyo`enai: Hodavyah, and Elyashiv, and Pelayah, and `Akkuv, and Yochanan, and Delayah, and `Anani, seven.

(1 Chronicles 3:17-24 HNV, boldface and underlining added)

I specifically quoted the Hebrew Names Version because the Hebrew names are the important information. But before we get to that, note that the family line follows Yekhonyah (Jeconiah), Pedayahu (Pedaiah), Zerubbavel (Zerubbabel), Hananyah, Shekhanyahu, Shemayah, Ne`aryah, Elyo`enai, and ends with Elyo`enai’s children — giving us the first 8 generations after Jeconiah. This tells us that by the time the book of Chronicles was completed, Jeconiah already had 8 generations of descendants. Of course, this is possible by the chronology I lay out in Appendix D of my upcoming book: I hold that Jeconiah was taken captive to Babylon around the beginning of autumn in 545 B.C. (which was the 8th year of Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign — 2 Kings 24:12 — by my chronology, which has Nebuchadnezzar’s first year starting in 552 B.C. {HIDMF p. ###}; note that 2 Chronicles 36:10 says Nebuchadnezzar took Jehoiachin captive to Babylon and put his uncle Zedekiah on Judah’s throne “At the turn [or “expiration”] of the year” — NKJV), and was apparently childless at the time, since he’s mentioned as having a mother and wives, but not any children in 2 Kings 24:12-16. I also hold that Nehemiah died within the first year or so of the reign of Darius II (Nehemiah 12:22c) around the end of 356 or beginning of 355 B.C. {HIDMF, p. ###} — 189.5 years later, which is certainly enough time for 8 generations of people to be born (it works out to a new generation starting every 189.5/8=23.6875 years on average)! Indeed, this is my main reason for thinking the book of Chronicles was finished by Nehemiah (though most likely started by Ezra, who tradition names as the author). Moreover, given this rate of new generations being started, how many generations would we expect between 545 B.C. and 3 B.C.? 8÷189.5×(545-3)=22.881266… nearly 23 generations, lining up very well with the 20 generations Heli was down from Neri (and by implication, the 22 Jesus was down from Neri) in Luke’s genealogy!

However, note that Pulliam made no effort to compare the line given in 1 Chronicles to the ones in Matthew & Luke. Showing the generations side-by-side reveals a major problem with the argument he’s making for the Zerubbabel in Matthew & Luke’s lists being Pedaiah’s son, rather than Shealtiel’s (the Greek spellings given are in NA28, the translation base for the 2020 NASB; alternate spellings are indicated afterward):

| Matthew 1 (Greek) | 1 Chronicles 3 (LXX) | 1 Chronicles 3 (MT) | Luke 3 (Greek) |

| Jechonias (Ἰεχονίας) | Jechonia-asir (Ιεχονια-ασιρ) (it seems the LXX translators understood Asir as a proper noun instead of a common noun) | yᵊḵānyâ ‘assir / Jechoniah the prisoner (יְכָנְיָה אַסִּר) | Nēri (Νηρὶ) |

| Salathiēl (Σαλαθιήλ) | Salathiēl (Σαλαθιηλ) | pᵊḏāyâ / Pedaiah (פְדָיָה) | Salathiēl (Σαλαθιὴλ) |

| Zorobabel (Ζοροβαβέλ) | Zorobabel (Ζοροβαβελ) | zᵊrubāḇel / Zerubbabel (זְרֻבָּבֶל) | Zorobabel (Ζοροβαβὲλ) |

| Abioud (Ἀβιούδ) | Anania (Ανανια) | ḥănanyâ / Chananiah (חֲנַנְיָה) | Rhēsa (Ῥησὰ) |

| Eliakim (Ἐλιακίμ; TR Eliakeim Ἐλιακείμ) | Sechenia (Σεχενια) | šᵊḵanyâ / Shechaniah (שְׁכַנְיָה) | Jōanan (Ἰωανὰν; TR Jōanna Ἰωὰννα) |

| Azōr (Ἀζώρ) | Samaia (Σαμαια) | šᵊmaʿyâ / Shema`iah (שְׁמַעְיָה) | Jōda (Ἰωδὰ; TR Jouda Ἰουδὰ) |

| Zadōk (Σαδώκ) | Nōadia (Νωαδια) (It seems the LXX translators misread ר (ρ/r) as ד (δ/d) – a common mistake, even in modern Hebrew!) | nᵊʿaryâ / Neariah (נְעַרְיָה) | Jōsēch (Ἰωσὴχ; TR Jōsēph Ἰωσὴφ) |

| Achim (Ἀχίμ; TR Acheim Ἀχείμ) | Elithenan (Ελιθεναν) | ‘elyôʿênay / Elio`enai (אֶלְיוֹעֵינַי) | Semein (Σεμεῒν; TR Semei Σεμεΐ) |

| Elioud (Ἐλιούδ) | See v. 24 here; none of the 7 names come close | See v. 24 here; none of the 7 names come close | Mattathiou (Ματταθίου) |

Clearly, the two lists here that are the closest matches are Matthew 1 & the Septuagint version of 1 Chronicles 3; and even then, only the first 3 names match: Jechoniah, Shealtiel, & Zerubbabel. Every generation after Zerubbabel is different in all 3 lists!

Also, that entry Pulliam cited from the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, while acknowledging that “The authorities have been divided as to whether Luke’s genealogy is Joseph’s, as appears, or Mary’s”, nonetheless sided with me that the evidence favored the idea that Luke’s account gives Mary’s line as the blood line; in fact, it presents no argument in favor of Luke giving Joseph’s line without subsequently saying that said argument has been put to rest! Indeed, the article failed to point out that Matthew’s Gospel was intended to present Jesus as King to the Jews (and so traced his right to the Davidic throne and his identity as the “seed” of Abraham), while Luke’s Gospel was intended to present Jesus as Ideal Man to the Greeks (and so traced his biological descent all the way back to Adam, the progenitor of all humanity and the original “Ideal Man”; see also 1 Corinthians 15:45); Matthew and Luke used the lines that were best-suited to their respective purposes — meaning Luke’s account must be giving the biological line through Mary! (Likewise, the nativity accounts in Matthew & Luke respectively give us Joseph and Mary’s sides of the story, so why wouldn’t the genealogies be respectively theirs, as well? I could go on about the evidence that the genealogy in Luke gives the line of Mary’s father Heli, but that ISBE entry and this article {scroll to “b) The genealogies:”} do a good enough job of it for me.) As for 1 Chronicles 3, that was clearly following the line of whichever son made their father a grandfather first — which wasn’t necessarily the firstborn (after all, my younger sister has a two-year-old son and just might have given birth to her second son by the time you read this, but I’m childless as of this writing!); apparently this portion of the book of Chronicles was being updated as each new generation started, because the children of only one son are named per generation. Since the royal line follows the firstborn of the firstborn of the firstborn, etc., simply assuming that Pedaiah had his son Zerubbabel before Shealtiel had his son Zerubbabel completely resolves the difficulties the lists in Matthew & 1 Chronicles otherwise present for each other.

You read that right: I believe there were 2 Zerubbabels in the same family; in fact, I believe that these 3 passages are referring to 3 different men named Zerubbabel (and 2 different men named Shealtiel)! You may think that’s ridiculous, but it’s perfectly reasonable once you consider what these names mean in Hebrew. Remember, Israelite children were generally named for their parents’ sentiments around the time of their birth. The name Shealtiel (H7597) means “I have asked God”, and the name Zerubbabel (H2216) means “sown (i.e., begotten) in Babylon”. There would’ve been a lot of Jewish parents with these sentiments during the Babylonian exile, so these would’ve been very common names during that period! “Zerubbabel ben Shealtiel” may have been the Exilic Jewish equivalent of “John Smith” {and those are just the ones mentioned on Wikipedia}! More practically, the Shealtiels (er, Shealtielim?) could’ve been distinguished from each other during their lifetimes as “Shealtiel ben Jehoiachin” (the one in Matthew & 1 Chronicles) and “Shealtiel ben Neri” (the one in Luke). Likewise, the Zerubbabels (Zerubavelim?) referred to in 1 Chronicles, Matthew, & Luke could’ve been respectively called “Zerubbabel ben Pedaiah” (assuming the Masoretic Text correctly identifies this Zerubbabel’s father; indeed, if the Septuagint version of 1 Chronicles 3:18-20 had the correct reading, it’s hard to believe that no names remotely similar to “Abioud” or “Rhesa” would be in that reading’s list of this Zerubbabel’s children {see the first 3 lines in the first column on p. 9}!), “Zerubbabel ben Jehoiachin” (after his grandfather; note that this Zerubbabel was in the royal line, and so naturally would’ve been called after his last ancestor to sit on the throne), and “Zerubbabel ben Neri” (after his grandfather) during their lifetimes.

In short, Pulliam’s argument that the Shealtiel and Zerubbabel in Matthew and Luke’s lists were the same father-son pair is nowhere near airtight.

But, for the sake of argument, let’s suppose that they were, and that Mary was a descendant of Jeconiah, just like Joseph. Jesus would still be exempt from the curse on Jeconiah in this scenario because of his virgin birth. Why? Because Jewish law and tradition reckoned generational curses as following fathers, but not mothers. Remember how Solomon was allowed in the temple he built, despite being only 4 generations down from a native of Moab (his great-great-grandmother Ruth)? Why was that the case if neither a Moabite nor the first 9 generations of their descendants was allowed in the temple/tabernacle (Deuteronomy 23:3-4)? Because Ruth was a Moabitess (note that the words for “Ammonite” and “Moabite” in verse 3 are both masculine, whereas the term for “Moabitess” in Ruth 1:22 is feminine), and so was allowed in immediately — and the Talmud affirms this understanding of Deuteronomy 23:3-4! Likewise, remember how God cursed the priestly line of Eli in 1 Samuel 2:31-36 so that “an old man will not be in your house forever” (verse 32c 1995 NASB)? I thought for the longest time that this punishment was too harsh, since it affected people who were far removed from Hophni & Phinehas’ iniquity. But once I learned this point about generational curses within the context of Jewish tradition, I realized that since this curse was only passed down to sons of sons of sons…of Eli, the only descendants of Eli who would suffer this curse of dying young were also the only ones that were eligible to be high priest (the office that Eli’s sons Hophni and Phinehas had profaned, thereby bringing this curse on themselves and their own descendants — remember, 1 Samuel 4:15-18 tells us Eli himself lived to be 98). This meant that none of Eli’s female descendants would be under this curse, nor would any sons those female descendants bore to a man who himself wasn’t under Eli’s curse.

For the same reason, if Mary’s father Heli was indeed a descendant of a strictly male line of Jeconiah, then Mary herself would be exempt from the curse on Jeconiah — as would Jesus and Jesus’ sisters (Mark 6:3), despite the latter undoubtedly having Joseph as their biological father. On the other hand, Joseph & Jesus’ younger brothers would’ve been subject to that curse, as would any sons (but not daughters) his brothers might’ve had.

In summary, Pulliam’s argument that Jesus can’t rule on Earth because he’s stuck under the curse on Jeconiah is flawed on so many levels that the alternative hypothesis — that the Messiah, Jesus, will reign on Earth someday (which should actually be considered the null hypothesis, since it was the one Jews have always held about the Messiah, and how the earliest Christians understood prophecies about the Messiah’s Kingdom; an alternative hypothesis is one that’s seeking to replace the null hypothesis that was held earlier, so the idea of a heavenly destiny and a current rule of Jesus from heaven that will never come to Earth is technically the alternative hypothesis in this case, since it came along over a century later due to Gnostic influence) — is perfectly viable, after all.

Conclusion

That actually brings out a supreme irony in something Pulliam says when bringing this up again in Lesson 15, when trying to explain away prophecies that place Christ’s future Kingdom on Earth:

One final detail needs to be revisited before we move on. One of the major goals of the Dispensational Millennium is to get Jesus Christ on the throne of David in the city of Jerusalem. Let’s review the conflict this creates with other passages of Scripture.

We learned in lesson 8 that Jesus Christ is presently on the throne of David. [I’ve already debunked Pulliam’s claims on that point here.] We also learned how New Testament authors stated that His “throne” at God’s right hand was the prophetically intended position (lesson 12). Also significant is the fact that Jesus Christ cannot reign upon the throne of David in Jerusalem and prosper (proven in lesson 9) [which I disproved in the above discussion]. All of this provides the following logic:

Major Premise: The Dispensational doctrine of a Millennium requires that Jesus Christ reign on David’s throne in Jerusalem.

Minor Premise: Jesus Christ cannot reign in Jerusalem and prosper, due to the curse of Jeremiah 22.

Conclusion: Therefore, the Dispensational Millennium is an error.

No matter how much a passage may look like paradise on earth, if our interpretation contradicts the remainder of Scripture, then we have misinterpreted the text. The problem is not found in God’s promise. The problem is found in details forced upon God’s promise to reformulate the overall design of God’s purpose.

{“In the Days of Those Kings”. 160-161. Italics, boldface, indentation, and contents in parentheses in original. Underlining and contents in brackets mine.}

Since Pulliam’s “Minor Premise” is false, the syllogism collapses. Dispensationalism overall may be in error, but the Millennial Kingdom being on Earth is not. And again, any claim otherwise contradicts Hebrews 2:5, the Greek text of which clearly mentions “the inhabited land, the coming one, about which we are speaking”. In reality, Pullliam is the one engaging in eisegesis — forcing details “upon God’s promise[,] to reformulate the overall design of God’s purpose”, by trying to force-fit the Scriptures to the presumption of a “heavenly destiny” for the redeemed. A Millennial Kingdom on Earth contradicts Plato, but not the Bible. At least the premises I’m using to fit all of Scripture together are Biblical, rather than pagan.

- Unfortunately, not all instances of “forever and ever” in English Bibles are translated from exactly the same Greek phrase. In Ephesians 3:21 (“to Him be glory in the church by Christ Jesus to all generations, forever and ever. Amen.” – NKJV), for example, the emphasized phrase was translated from “εἰς πάσας τὰς γενεὰς τοῦ αἰῶνος τῶν αἰώνων”; literally, “unto/for all the generations of the age of the ages”. Note that the latter instance of “of the age” is plural, whereas the corresponding instance in Hebrews 1:8 is singular. This implies that the time period being referred to in Ephesians 3:21 includes not only the one referred to in Hebrews 1:8, but also other time periods (namely, all other periods of history during which humans ever have had and ever will have children). Yet most English translations indiscriminately translate both as “forever and ever”. Hence, exactly which time period an instance of “forever and ever” is referring to can only be determined by checking the underlying Greek text. ↩︎

- As for why only 5 sons are listed when the sentence ends by saying there were 6, I’ve seen a handful of explanations. James Burton Coffman suggested that the words וּבְנֵי שְׁמַעְיָה (“and the sons of” and “Shemayah”) were accidentally duplicated from the first part of the verse at some point, in which case Shemayah and the 5 names following him were the “six” sons of Shekhanyahu. Alternatively, Albert Barnes pointed out that the “Syriac anti Arabic” adds “Azariah” between “Ne`aryah” and “Shafat”. Not sure whether “Syriac anti Arabic” referred to the Syriac Peshitta or not, I decided to check for this Azariah’s presence in an English translation of the Syriac Peshitta of Chronicles {after clicking the “DOWNLOAD PDF ORIGINAL”, scroll to p. 468 for the Syriac text and p. 467 for the English translation.}, which has been the standard OT translation of Syriac churches since circa A.D. 200, being an Aramaic translation of a 2nd-century Hebrew text; sure enough, “Azariah” is in the English translation (although other names are different, no numbers are present, and the sons from verse 24 are included in the same sentence). However, such an omission must’ve first occurred at least 400 years earlier, since manuscripts with five names after “Shemayah” were already circulating by the time Chronicles was translated into Greek (the LXX includes “and sons of Samaia” and “six”, yet also lists only 5 names). Still others would rather retain the Hebrew text as it stands, but take the “six” as referring to sons of Shekhanyahu, with Shemayah and his five sons being counted due to Shemayah being an only child; this possibility has the added benefit of explaining why the instance of “sons” before Shekhanyahu is also plural in the Masoretic Text (albeit singular in the LXX). Now, if we redo the calculations in the paragraph following my quotation of 1 Chronicles 3:17-24, but with the average generation time implied by only 7 generations being listed, we’d expect Luke to list Jesus as being 20.021108… just about 20 generations down from Neri, rather than the 22 actually listed! Therefore, I find the latter 2 possibilities (i.e., either one of Shemayah’s sons’ names dropped out of the Hebrew text, or the text is counting all the sons of Shekhanyahu’s only son along with the only son himself) to be more likely (although I’m personally leaning toward the last one). So my table in this blog post coheres with those possibilities, in which case there were 8 generations of Jeconiah’s descendants in 1 Chronicles 3 instead of 7. Of course, comparing the names at both hyperlinks in the final row with “Achim” and “Semein” shows that the alternative doesn’t improve the fit of 1 Chronicles with either of the Gospel genealogies! ↩︎